|

|

|

| Subscriptions click here for 20% off! | E-Mail: info@rangemagazine.com |

|

|

||||||||||||||

Sad, Mad Days at Black Rock

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| A couple miles north of Gerlach the pavement stops, offering a

choice between a rocky jolting route on the “high line” alongside the Calico Mountains, below, or in dry weather, busting out in a sharp right on to the shimmering white Black Rock Desert playa. |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Western Pacific freights bound for the Feather River still howl

with heavy metal screeching into Gerlach like they own the place.

It hasn’t been a railroad company town since the 1970s, but Gerlach

holds on, like a welcome green wart on the smoothly blinding white

playa of the Black Rock Desert. Some say Bruno Silmi owns the

town now, or most of it anyway. For sure, it’s Bruno’s bar and

restaurant right across from the tracks that is today as much

the definitive character of the town as Western Pacific ever was,

and Bruno himself is its thickly accented image. The old Italian

has been here since the ’50s, expanding a little desert empire

in property and livestock with a godfather style as stubbornly

personal as the accent itself. “Everybody in Miami. In Florida,” Bruno bursts out in a perplexing declaration of the argument. “Ever see any demonstrations here in Gerlach? No, you never see it. But they do it anyway. What kinda government we got here?” His daughter Courtney, or “Skeekie” as everybody knows her, sometimes translates the Bruno style for particularly lost-looking travelers, bu these days when most people have heard about the proposed National Conservation Area (NCA) designation for the Black Rock she only has to wait for the light to dawn in their eyes. “We see ’em all. People with clothes, people without clothes. People who have race cars, people who don’t. People who know enough to carry water, and people who are lost all the time. In the last six months we’ve seen more and more people who come by just because they don’t think they’re going to be allowed to see it anymore.” No matter what retiring Nevada Senator Richard Bryan says about his NCA legislation including provisions keeping it open for all sorts of uses from rocket racing to cattle grazing, Bruno’s common sense about government action connects like a clank in the coupling. More government means less access. The feds are trying to close the Black Rock. Gerlach is only the beginning. People buy road cups and tee shirts here with Bruno’s slogan about it being “Where the pavement ends and the West begins,” but they don’t all grasp how seriously or even how sentimentally that is true. Only a couple of miles north of the town, the pavement does stop, offering a choice between a rocky jolting route on the “high line” alongside the Calico Mountains or, in dry weather, busting out in a sharp right onto the shimmering white playa itself, so vast and so flat that you can begin to see the curvature of the earth before it reaches the distant eastern monoliths of Black Rock itself. It is the same place where vehicles fired by fiercely-powering jet engines strive to break the sound barrier on wheels, or where amateur rocketeers send vehicles of their own into near orbit, but it is mostly and fearsomely empty, a hard pan smoother and enormously wider than any imaginary turnpike that despite the chalky clouds tracing a passage, seems never even to reveal a rut or track from the wheels that cross it. To the emigrants who faced it on their way West in the mid-nineteenth century, it must have seemed terrifying. Like a satanic sheet ironed in heat and full of illusionary mirages, crossing the Black Rock was as much as sliding a hand over smooth white death. Last Labor Day, some 25,000 people, “some with clothes, some without” took part in the annual “Burning Man” celebration of wildly eclectic art. By spring, there is almost no trace they were there, except that tedious negotiations with federal and local officials in board rooms miles away go on about plans for this year, and next. Bryan’s bill to “protect” the Black Rock wants to assure that “Burning Man” will be allowed to continue, just as will be the late spring efforts to break the land speed record, or the drives later to move cattle to higher summer range. Nothing, Bryan insists, would be eliminated by a new designation. All the law that ever there was in the Black Rock will remain, without new regulations over existing uses. It would only be with new authority. To protect it, Bryan says. Fifteen or 20 miles of pilot-speed travel across the great playa brings you to a single pole anchored to an old tire signaling access back to the rocky road. Too much is made of the obvious white agony of the Black Rock’s bottom, when in fact most of it in Bryan’s proposal climbs and rolls in a carpet of green sage and juniper enlivened in springtime by dashes of orange and yellow blossoms. Riding a corral fence another 10 miles beyond the playa is a lonesome-looking young buckaroo named Jacob William Gardenhire who along with his mom and dad and four brothers and sisters lives on the Wheeler Ranch. “Well, not much to do,” admits 12-year-old Jacob, who is home-schooled and makes it to the town of Gerlach only about once a month. “Except the horses. I like the horses. And the hot springs to swim.” Not everybody would choose to live out here, and not every kid will choose to stay for long. But north of Black Rock itself is as truly the West as anywhere it can still be found, a place of opal miners and unique characters, small ranchers and roaming romantics. No stores, no power lines, not a lot of water. And this is where Bryan’s NCA is most unwelcome. In the 1960s, Jim Linebaugh was an idealistic and somewhat itinerant employee of the U.S. Department of Agriculture involved in a project for resource restoration and development in California and Nevada. From the explorations of John C. Fremont and Kit Carson in 1844, the trails west were at least generally known. Fremont passed south from Oregon though the Black Rock region to Pyramid Lake, despairing at times from the loss of pack animals and the absence of game, taking bearings off steam vents that opened in the fog that plagued his January march. But the foundations of routes to California and Oregon were laid by his mission. When Linebaugh began his work, the basic routes of the later Lassen, Applegate, and Noble trails were known, but little attended, until he began revisiting them. Linebaugh today is an ardent opponent of an NCA designation for Black Rock, yet in a way, it was his fault. From his work with USDA in rediscovering trails–that over the last half of the nineteenth century up to as late as 1911 saw passage of at least 150,000 emigrants–there evolved the foundations of Trails West, an informal club of people mutually interested in preserving the almost-forgotten routes through forbidding deserts and canyons that constantly concealed the threat of attack by native Paiute and Shoshone warriors. It is almost the ultimate romantic image of the West, still to be seen today in an 1853 signature etched in canyon stone or in slowly fading names and dates written with axle grease in an ancient Indian cave. These were the things Trails West began rediscovering in their weekend outings during the late 1960s and ’70s. Among the most dedicated of members was the distinguished Robert S. Griffin, Ph.D., a professor of speech and debate and Dean of Students at the University of Nevada, Reno. Dr. Griffin was an enthralled scholar of the Fremont expedition, and he and his wife, Marguerite, were absorbed in the task of marking the old trails for future generations. In 36 years of a political career that brought him from the state’s attorney general, to governor and finally to the U.S. Senate, Richard Bryan had certainly visited Gerlach, the Black Rock Desert and High Rock Canyon on more than one occasion. But Bryan, a Las Vegas native and son of a successful attorney, was never an outdoorsman of the kind who would trek along with Trails West. His chief connection to the old trails came from his time as student body president at the University of Nevada and the mentoring relationship established then with his father’s former professor and the debate coach with whom he so closely worked, Dr. Robert Griffin. Griffin had a personal magnetism, especially in a time when the Silver State had a resident population smaller than the gambling crowd on any good weekend. At UNR, there was a unique sense of purpose among the students who meant to make more of their Nevada pride. So it was not surprising that Bryan’s teammate on the debate team was Jim Santini, who would become the state’s lone member of Congress. In those days, the circle of friends with serious thoughts was almost family-sized in Nevada, and meant to last a lifetime. Setting aside the Black Rock as a special place stems from that, and from the beginnings of Trails West. If you can reach it on the rocky and rutted jeep trails climbing more than 60 miles beyond the playa, their patient voluntary work can be found in simple iron rail markers designating a trail followed by people who themselves must have hurried by this desert as much as they could in the struggle to reach a western promised land. To protect them from canyon ambushes and willow-screened attacks on their livestock by the Paiute, federal authorities in 1864 established a cavalry outpost in a green and watered cusp of a valley known as Soldier Meadows. The last of any real road ends there today. All around, to the north and the west and the east, the open mountains seem to shelter history with mysterious dreams of blue shadowed gullies and deep green slopes where perhaps none beyond the Paiute themselves have yet ever been. To the distant south and turning west beyond the pools of hot springs slowing the iron brown creeks is High Rock Canyon. The old stone buildings of the federal outpost are still there at Soldier Meadows. The pleasantly shaded old officer’s quarters disguises a tunnel beneath the fireplace that leads to the stables, meant for use in a major Indian attack that never came. Ironically, though, Soldier Meadows is today a center core of private land surrounded by the empty expanse of federal territory around it. On his 12,000 deeded acres, rancher John Estill carries on a struggle for survival curiously reversed from the intent of those sent to build this old federal fort. Estill rides in after dark, along with the hands he had with him in the long day of rounding up cows and their calves for the branding that will begin at dawn. “This business has been risky since the Civil War, man,” said Estill, dropping himself in a dusty heap on a couch after dinner, “and I think we lost that one.” He is a young man, not yet in his forties, but he carries six generations of ranching, mostly in California but all the way back to Daniel Boone, with him. Soldier Meadows has been his for the last three years, and so far, the economics of his calf production has proven far more encouraging than the frustration of political consequences he had not anticipated. “Good times, bad times, we can handle that. It goes with the business. It’s the politics, and I guess we won’t know about that until November.” Estill is married to Jim Linebaugh’s daughter, Lani. They met while she was studying agricultural economics at UNR. Their livelihood and their future may depend on the status of the enormous federally held lands all around them. Other ranchers are at risk as well, but Soldier Meadows is almost dead center in the more than a million acres of land that could be taken up in an NCA. Senator Bryan, in his public statements, has insisted that grazing rights will be assured, but the evidence of what has happened in other NCA’s suggests slow strangulation of working ranches. “There’s no reason for it,” Estill says, repeating the logic of many. “The BLM is already here, and the EPA and Fish & Wildlife, Nature Conservancy, you name it. High Rock [Canyon] has already been bought out of all grazing permits. One more level of federal designation either means nothing–or something.” People still leave their signatures and simple messages in High Rock Canyon, although these days they are scribbled onto the sheets of yellow lined legal paper left in a metal box for visitors. Most speak about the spectacular beauty of the place, but many are also meant as a ballot, proclaiming in large letters, “NO TO AN NCA.” High Rock won its way into special federal designation as an Area of Critical Environmental Concern (ACEC) in 1994 after a half-hearted attempt by Bryan two years earlier to introduce an NCA covering the entire area. It had Bryan’s name on the legislation, but the background for it came in a division of Linebaugh’s old Trails West group soon after one of the members, Susan Lynn, left her job as a staffer for the former Congressman Jim Santini. She and Linebaugh still count themselves as friends, though on opposite sides of the future for a region cherished by each. “I just don’t think people know how to behave up there anymore,” she said. “I’m afraid we’ll either love it to death, or beat it to death.” It was the sort of worry said to have been expressed by Dr. Griffin as he witnessed the startling growth of Nevada’s population beginning in the 1980s. When Griffin died in 1989, Senator Bryan was among the mourners. In the years that followed, Bryan related to Lynn and others the personal promise he made to Griffin’s widow, Marguerite. It was to win protection for the Black Rock. Bryan had always been a people’s politician, making it a point at least annually to spend some time in every rural district, hearing the problems of the locals, helping their kids when he could. When he announced in 1999 that he would not seek a third term in the Senate, he let it be known that his last two years in office would be devoted to two causes in particular, one in stopping the storage of nuclear waste in Nevada, and the other in preserving the Black Rock/High Rock region from what he said was the growing threat of destruction by Nevada’s burgeoning population. Many saw it as an attempt by Bryan to establish his own legacy from the Black Rock. A few who knew the whole story wondered if it wasn’t meant as a promised legacy in memory of Griffin. At the news conference announcing his NCA legislation, they noted that Marguerite was with him. Whatever his motivation, an NCA made little sense to people who already recognized the Black Rock as protected by books of federal regulations covering its uses, and even alarmed by the public attention Bryan was calling to it by his campaign to add a new designation. Twelve of 17 county commissions in the state issued resolutions in opposition to the designation, and statements from all the others, except Las Vegas’ Clark County, offered him no support. Republican Governor Kenny Guinn sent a letter to the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources strongly objecting to the NCA proposal as unnecessary and, “taking place without local involvement.” Though he would later testify in favor of the measure, the state’s other U.S. Senator, Harry Reid, pronounced Bryan’s bill as hopeless from its introduction. Yet Bryan pressed on, for once ignoring many of his old local supporters and divided friends, and calling upon polls done by the spin doctors of Bill Clinton himself that suggested three quarters of recently urbanized Nevada supported the measure. Bryan presented statistics claiming that 35,000 visitors had been there in the last year, even though he knew that at least 25,000 of those were at the three-day “Burning Man” event far from any threatened trails. Using logic in both directions, Bryan insisted that growth in the state posed risks to the region, and at the same time that the sprawling urban populations of Las Vegas and Reno were behind him in wanting it protected, despite rural objections. |

||||||||||||||

| Whoever Bryan may be listening to from the urban-centered environmentalist

movement, most of those who truly know the Black Rock cannot understand

why the senator wants to add another layer of federal regulation. Before dawn, Estill and his wranglers have saddled up again at Soldier Meadows. This will be a branding day, done the old-fashioned way with lariats and hot irons, muggers and sharp knives. Donna Potter has been to one of these in this last year of her education as a resident of the Black Rock. Raised as an ardent environ-mentalist and lifelong vegetarian, “I thought of cattle guys as big corporate mongers exploiting the land and the animals,” she said. “But when I met them they were generous and kind people, and what they said just made common sense.” Potter came from Los Angeles to become the environmental coordinator for Empire Farms near Gerlach, the largest producer of garlic seed for California. Empire Farms, sweetly settled on the southern edge of the great playa, would not directly be affected by the NCA, but its owner, Mike Stewart, and its environmental spokesperson, Donna Potter, are among the most prominent of the scores of people and businesses in the region on record in more than six pounds of paper opposing Bryan’s NCA bill. |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

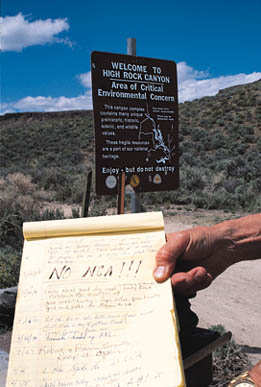

| Sentiments are clear among desert dwellers, "No NCA!" | ||||||||||||||

|

“I don’t know why it goes on,” she said. “We’ve offered to bring

everybody together for some compromise, maybe even some way to

pass on the legacy, but the senator (Bryan) won’t even respond

to us.” Potter, by the way, remains a vegetarian, and though they

don’t share the same view on the NCA, she has become a friend

of Susan Lynn. Tim Findley is an investigative reporter who has worked for the San Francisco Chronicle and Rolling Stone. He lives in Fallon, Nev., and warns, “Don’t go out on the Black Rock Desert unless you are prepared.” |

||||||||||||||

|

To Subscribe: Please click here for subscription or call 1-800-RANGE-4-U for a special web price Copyright © 1998-2005 RANGE magazine last page update: 04.03.05 |

||||||||||||||