|

|

|

| Subscriptions click here for 20% off! | E-Mail: info@rangemagazine.com |

|

|||||||

|

The U.S. By Tim Findley |

|||||||

| However much most of the nation might ignore or be indifferent to another confrontation over federal grazing, the dark end of the dispute might be foreseen in the Ruby Valley, Nev., rancher likely to become its first political prisoner. | |||||||

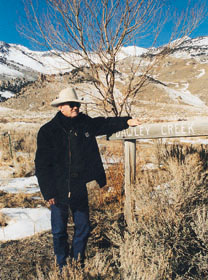

| Cliff Gardner © Mary Branscomb | |||||||

|

Cliff Gardner is due to be sentenced on federal trespass charges February 21 after a six-year-long battle over his grazing rights on Forest Service land in the remote mountain valleys of Northeast Nevada. He could face up to a year in prison and $10,000 in fines. He is not expected to go quietly. A third-generation rancher whose ancestors were among the first to break ground among the Shoshone and Paiute in the high desert some 100 miles from the nearest town of Elko, Gardner was raised with the land, bitterly regretting even the childhood years when he was sent away for schooling. As unlikely and as unwilling as any cowboy to become an intellectual, Gardner has since plugged himself in to a study of constitutional law as a means of self-defense and to a one-man show of photographic record to demonstrate that managed grazing has benefited, far more than harmed, the ecology of the Silver State. He had not planned, or been formally educated to become a thorn in the federal backside, but the forest rangers he knew and admired as a kid turned against him in the ’90s when they claimed he was overgrazing his allotments and set out to shut him down, a piece at a time. Like a field laboratory test of what environmentalists now outline as a future for the West, Gardner faced loss of his historic grazing ground, cranking economic pressure on his family, and the persistent lure of The Nature Conservancy’s big money to buy him out. Going it alone even against the more cautious dissent of his neighbors, Gardner defied them all, claiming that constitutional provisions under the Fourth Amendment established his rights to put his cattle out on Forest Service ground. There were warnings and threats and lawsuits, and The Nature Conservancy always offering to solve it all. Last August, after he’d taken 200 head down from 50 days on Harrison Pass, he saw the uniformed agents up there with their clipboards and pens and recognized many of them. Gardner knew what was coming. As it has been for years, it was their evidence against Gardner’s. He had photos to show the grass was back up in weeks; they had notes claiming the stream banks were broken down. But damage wasn’t really the issue. It was Gardner’s defiance of authority in “unmanaged grazing” on public land that quickly convicted him. “Sure, they mean to make an example of me,” said Gardner. “One way or another, I can be used to send a message.” It’s the means of the message that may prove most important in this test-case history of what may be ahead on public lands. Gardner has spent 20 years compiling more than 1,300 slides and posters and stacks of documents he has used in presentations wherever he has been invited to demonstrate that halting grazing in the Ruby Mountains reduces water flow, decreases insect population, gradually closes out sunlight and eventually results in far less diversity of plants and wildlife. If Federal District Judge Howard McKibben gives him the chance at his sentence hearing Feb. 21, Gardner will present that same evidence again, along with the arguments from some 60 federal court cases he feels support his right to graze on land sealed by federal authorities without regard to the constitutional rights of state citizens. McKibben, however, isn’t known for such generous jurisprudence, so Gardner has already set up yet another tour for his lectures, covering Nevada, California and at least New Mexico in the weeks before the hearing. Gardner and his family could probably walk away from it all. They could sell to The Nature Conservancy and probably live comfortably in one of the towns he has always avoided. In any case, it may be unlikely that the judge will actually send him to prison rather than some form of house arrest. After Gardner, though, there are others such as Cliven Bundy of Southern Nevada and even Wayne Hage in Central Nevada who have shown similar defiance of presumed federal authority. Through a dark glass, the United States vs. Gardner may be a dim view of the near future. |

|||||||

|

To Subscribe: Please click here or call 1-800-RANGE-4-U for a special web price Copyright © 1998-2005 RANGE magazine For problems or questions regarding this site, please contact Dolphin Enterprises. last page update: 04.03.05 |