|

|

|

| Subscriptions click here for 20% off! | E-Mail: info@rangemagazine.com |

|

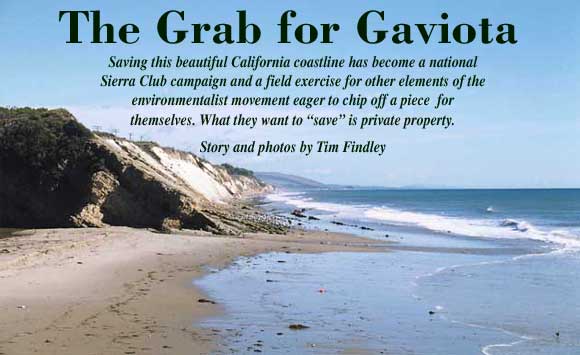

As if from the hand of a master still unsatisfied with his canvas, light strokes of fog reach up from the Pacific Coast, following the canyons to a wispy tumble across the uppermost ridge of the Santa Ynez Mountains. It is a gorgeous blue-green panorama etched in white diagonals tracing contours all the way north from Coal Oil Point in Goleta to Point Sal beyond Vandenberg Air Force Base. The Western White House, Rancho del Cielo, used to be there at the top of the ridge. It was the place chosen by President Ronald Reagan as his personal retreat. In 1983, during the sort of gully-washer storm that periodically floods stream crossings on Refugio Road, the president waited as Secret Service agents transferred Britain’s Queen Elizabeth from her limousine to a four-wheeler made as comfortable as possible for the last of the steep, jolting ride from the coast. They say the queen’s face grew increasingly dour through the lunch of barbecue and chili, and the next day, when the weather was clearing and the landscape was littered, as it often is, by rainbows, the queen declined an opportunity to return by helicopter to the 688-acre Reagan Ranch. It was sort of an American frontier nudge at the ribs of proper English cousins. The stunning, unpredictable view from the edge of Manifest Destiny, reachable only by a narrow road barely tamed since it was a stagecoach route from the Central Valley to the coastal missions of Alta California. Jenifer McNabb still chuckles about the image of a sour-faced queen enduring a journey past Jenifer’s own spectacular home designed by Frank Lloyd Wright on the shortest slope down from the Reagan Ranch. “It was the way it should be,” she said. “The way it still is.” Sheets of windows form the oval outlook that absorbs her front room into the epic of sky, sea, and lush coastal growth below her. Yet, for a few days each year, she will be trapped in such grandeur by the sullen rage of steady weather. “I don’t want it made any easier, or any more accessible,” she said, “even for a queen.” It is not royalty that today worries most of the privileged and fortunate who own property along this 78-mile stretch of coastline reaching up to 20 miles inland north of Santa Barbara, Calif. It’s overly righteous young environmentalists in nearby student centers, a few local politicians with possible legacies on their minds, and an oddly self-professed ex-“Weatherman” who gets more credit than he’s due as the bad-guy bureaucrat behind it all. “Saving” the “Gaviota Coast” has become a national Sierra Club campaign and a field exercise for other elements of the environmentalist movement eager to chip off a piece for themselves. For the embattled landowners, it is a nightmare fantasy that redefines the coast and misses the point. Clacked together in a rough alliance, the mixture of farmers, ranchers, homeowners, and purely independent types have been forced to organize in a fight against “saving” a huge agricultural area already protected by an armada of local and state laws and regulations. None of them, not even the Reagans, has ever before referred to it as the “Gaviota Coast.” Coined (as most think it was) from cool air by a former head ranger of the tiny Gaviota State Park near the center of the region, the “Gaviota National Seashore” proposes an arms-wide reach to absorb them all in a federal domain unlike anyplace else except the Pt. Reyes National Seashore in Northern California. Defined that way or not, “Gaviota” would effectively create a new national park cut down its middle by the U.S. 101 freeway linking Mexico to Canada. Barely restrained on the southern boundary of the proposed new park is a Southern California multi-megalopolis numbering some 20 million people. The environmentalists, led by the Sierra Club’s newly designated “Gaviota Project,” say some sort of higher authority is needed to save the region from urban sprawl that will sooner or later overwhelm local laws. The people who live there and grow crops there say thank you very much, but they still have their own rights and their own regulations. Federal intervention however it is defined, they say, would trample a haven of historic custom and careful agriculture as valuable and viable now as it was before the American Revolution. The battle today, of course, can’t be fought without one side throwing in frogs and salamanders and snowy plover nests as well as three grass species they say are already endangered. Others agree that the species most at risk is rarest of all on this side of the Pacific—rural farmers and ranchers who still hold private property in the last of the “unprotected” coastal regions of Southern California. Former Gaviota Park Ranger Mike Lunsford didn’t really spring the grand conception out of his own head in the 1990s as some believe. He and others in the region had the experience of watching the coalition of forces in the Clinton administration aiming ashore at the mainland from their capture of the Channel Islands, 30 miles off the coast, in the early part of the decade. By 1997, the islands formerly dotted with farms and livestock including cattle, sheep, and horses, were in the hands of the Park Service and their larger-holding financiers from The Nature Conservancy. Fees and federal force on the islands had replaced fences no longer necessary. The livestock were gone. Visiting people needed a permit.

Gaviota, “Seagull” in English, was a clear day’s view away, at the center of an almost forgotten realm still holding the traditions of the great haciendas and fertile plateaus from the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. It still carried a certain charm of Spanish California as it was before the Gold Rush. Productive agriculture on private land there has continued over more than two centuries, longer even than many farms established east of the Mississippi. Best known among them is the vast Hollister Ranch, a surviving epitome of Spanish Land Grant holdings, right on the guarded fence border of the state park itself. History and culture, nature and native remains alone seemed to command preservation against the encroaching, relentless growth of suburban civilization beyond Santa Barbara. And yet, though Park Ranger Lunsford could certainly see the romantic values, some local lore insists it was actually sunblind surfer Bob Keats with an eye on private waves in the region who first began pushing the idea of a new park on the coast around 1994. Doesn’t matter, really. Whoever put the note in the bottle, the Sierra Club has it now and the green genie is loose. “We want to see a feasibility study by the Park Service and that’s it,” snapped Sierra Club organizer Ariana Katovich who works full-time on the project. “We’re not looking for another Yosemite on the Gaviota Coast, but who’s to say what local restrictions are there now won’t change in the political process? It needs protection. There are other possibilities beyond a national park or a national seashore. There are possibilities that haven’t even been thought up yet.”. One more slope down from Jenifer McNabb’s show home on the Santa Ynez ridge is the intentionally eclectic and mildly eccentric ranch house that Lanny Stableford and his wife Bernie built for themselves in a raw stretch of once-inaccessible land off Refugio Road. Heavily timbered by Lanny’s backbreaking work in levels to reflect the landscape, it still lacks some finishing touches of tile and trim from a job begun in the 1970s, about the same time that the Reagans found Rancho del Cielo. Roving bears and runaway bulldozers were part of the challenge, but now on his 500 acres Stableford produces a profitable crop of avocados, and Bernie takes special pride in the cantankerously independent herd of half a hundred longhorns that graze on the hillside. Arrayed for effect on the 15-foot electronic gate to their property, longhorn skulls suggest Bernie’s impish taste for the unusual. The Stablefords, relative newcomers to the classically Castillian region of rural Goleta, have become the primary motivators among neighbors up to 70 miles away whom they might never have met but for the proposal to begin a study of the “Gaviota National Seashore.” “It was just put there, period,” said Bernie, stabbing at a Park Service map that seemed to suggest the “Gaviota Coast” had been surveyed like a Spanish mission. “No real talks with anybody, no input. They just drew a line all the way up from the coast and across the ridge and presented it as a new ‘Seashore.’ Property owners, taxpayers, anybody else, weren’t asked. They just got the news.”. It was in March 2000 when the National Park Service opened its first “scoping” meetings on the plan, reaching with a full federal hand all the way to the Reagan property itself and on through the military base at Vandenberg. The few local property owners who attended sat initially stunned by the slim-choice options afforded to “save” their own land from a designation that suddenly appeared with new trails, campsites and parking areas that cut through even some of their own property. Nobody could remember being asked. Looking even closer, they noted that new lines down the ridge seemed to follow every single stream except the Santa Ynez River itself. Serious suspicion is that the “Gaviota Coast” was already on the short-stick list of possible new “monuments” that former Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt bragged he could present to President Clinton for approval by executive order anytime, regardless of local or even Congressional opinion. Babbitt did it that way all over the West at the end of his administration, but he apparently didn’t move fast enough on Gaviota. When he did appear in one of the local meetings on the issue last year, a young audience participant, apparently imbued with theories advanced in the United Nations, rose to say he felt that “private property today is an outmoded concept.” “Well, I might tend to agree with you,” the jowly former emperor of the Interior advised, “except for these two matters of the Constitution and the Fifth Amendment.” Ironically, Babbitt by then was on his new incarnation as a consultant to the Hearst Corporation trying to subdivide equally rich propery up the coast near San Simeon. If it turned out to be too late for a simple snatch by the outgoing president, even a study of the grand Gaviota fantasy proved to be too expensive for the Park Service alone to handle on its budget in the new administration. The fog might have taken it from there except for a letter sent by the Santa Barbara County Supervisors to Congresswoman Lois Capps suggesting she herself might want to introduce a bill to fund the Seashore study, and offering the help of the county if needed.

It was then that Bernie Stableford, whirling out of what she calls the “war room” of her hillside sanctuary, began forming the Coastal Stewardship Council among property owners, some of them fifth- and sixth-generation neighbors they had yet to meet. Tough to assemble among people who value their independence and their privacy, it was nevertheless a necessary answer to the freshly established Gaviota Coastal Conservancy which already proclaimed itself in charge of promoting “permanent protection” of the unique coastline, its wildlife, and its reluctant characters. John Buttney, a dapper-dressing administrative assistant to Santa Barbara Supervisor Gail Marshall who some call the “sixth” of five elected members to the county government, firmly remembers that he first heard of the Park proposal and the Coastal Conservancy around 1994. It was, he says, brought to meetings of the county planning commission, which Buttney effectively runs. He recalls absolutely that, “Farmers were there, and the [Santa Barbara] Farm Bureau knew all about it.”

Farm Bureau Director Leroy Scolari, however, just as firmly calls that, “Hot air.” The first he heard of it, third-generation farmer Scolari said, was with the rest of his neighbors, early in 2000. By then, there was no doubt that the Park Service had laid its plans and done its maps and helped create the Gaviota Coastal Commission. What probably prevented a blindside follow through was more the national election than any unheard local opposition. Rich as it might seem in movie star mansions and a University of California campus, agriculture is not just incidental in Santa Barbara County. It is the county’s major producing industry, valued at over $735 million in 2000—a $78 million increase over the previous year. Total contribution to the Santa Barbara County economy multiplies out to $1.5 billion a year. Most of that comes from the proposed “Gaviota National Seashore.” It seems unlikely that farmers would have sat politely while planning went on for six years to make them a national park. “Hot air,” Scolari calls that notion..

The farmers were, and are, Buttney’s own constituents in his job representing Supervisor Marshall. So, for that matter, is the nascent “Gaviota Commission.” An inveterate political operative seemingly hooked on the process, Buttney came to Goleta in the 1970s carrying, as they say in politics, “baggage of his own.” He had been an anti-war radical in the most intense regions of resistance around Michigan and Chicago during the street battles of the ’60s. He had an arrest record, and he admitted that for the little time it lasted in 1969, he was a member of the militant “Weathermen” organization. Although a mere nuance lost on most, it wasn’t until “Weathermen” became the “Weather Underground” that they began planting bombs in public buildings—something Buttney said he would have nothing to do with.

“When that came out, even the environmentalists wanted to distance themselves from my ‘radical’ past,” Buttney conceded. Still, when it seemed to be unraveling, it was Buttney who wrote the letter to Congresswoman Capps suggesting she seek funding for a study of the Gaviota Coast. Adding more complications, the Congresswoman had replaced her husband, a long-time representative of the area, who died in office. There was at least the hint that she might want his name attached to the legacy of a national park.

Not far below the whimsical big gate leading to the Stableford ranch off Refugio Road is a flat stretch with the reliable and clearly utilitarian ranch-style home of Les Freeman. Freeman’s family has been farming and ranching here for more than three generations. Avocados and lemons and all the exotics possible to grow in this lush region are still an exceptionally good cash crop, but Freeman’s land is in a drier zone, good for grazing, tough for cultivation, and Les was hard pressed to keep up after his brother decided to leave farming and sell out his share of the ranch. Heavily burdened already by inheritance taxes, Freeman was in danger of losing his 600-acre ranch unless he could somehow find the money to pay off his brother.

In other places, perhaps in other times, the lurking presence of a “willing buyer” like The Nature Conservancy might have seen Freeman’s situation as natural prey. He worked out a deal, however, with another group that emerged at about the same time. It was an agreement with the Santa Barbara Land Trust that seemed almost too good to be true. “Yeah, we argued and fought about restrictions and certain things, but it really has come down to us being under the same restrictions as Santa Barbara County has, with the exception that I won’t let the cattle in the creek, and we’ll protect the oak trees,” said Freeman. “Other than that, we lose the right to ever build houses on the land or develop any kind of subdivision, but we can work it, farm it—continue to live the way we have.” The Freemans got $990,000 to stay in business. There are places in the West where that might sound like a long-lost chapter of the “Wizard of Oz.” But in Santa Barbara County, the laws and regulations already in place not only favor agriculture, they make it almost impossible for any other use of private land except maybe by reclusive rock stars. Current zoning regulations restrict any new development in the agricultural area to a single family home on a minimum of 320 acres. Even property owned before the present code was enacted can’t be divided into parcels less than 100 acres per family home. That, in fact, is what began to happen behind the exclusive guarded gates of the old Hollister Ranch along the most barren part of the wind-swept coast. Here, 900 relatively new owners are riding out the current political storm brought in part by their presence. Under current statutes, however, Bernie Stableford’s estimate is that no more than 200 new homes could now legally be built on the entire coastal region.. Refugio Road never does get much better from its narrow, rutted ride even after you find your way down beneath the 101 freeway and through a canyon of eucalyptus to the serious gates of Los Dos Pueblos, a place some call the “Royal Rancho” of the Santa Barbara coast. This is the place that once and still puts the Hollister Ranch to shame. Rich in a private history of Spanish seafarers and piratical wealth in the 18th and 19th centuries, its remaining 3,000 acres hide a haunting memory of cultured grandeur. Even the eucalyptus date from a time when they were planted as potential poles to replace the masts of storm-wrecked galleons. What remains is a botanical garden only slowly ebbing from the time less than 50 years ago when it still provided exotic orchid-filled greenhouses and ambling aromatic lanes leading through tended orchards and old-growth trees to, among other charms, even a private zoo. It’s all still there, and although the cages are empty and the greenhouses blankly vacant now, the lawns and hedges and palms all gracefully groomed seem to be awaiting the arrival of the next carriage in the curved driveway of the unoccupied, but some say haunted, mansion. On the west, sheltered from view by thick orchards of avocados and surrounding oaks, there is still to be found with its intentional surprise the old private beach of the “Royal Rancho.” It seems perfectly preserved in its palm-bordered green veranda stepping down as from a wide cobblestone stage to a pristine stretch of fine white sand. Owner Henry Schulte likes this spot best. But he has always been disappointed by the waves. Even at 48, Schulte is at heart a surfer. “You’ve got to go a little north for the best curls,” he said with a little yearning. And he often does. Even if Schulte could get around county regulations and subdivide the 3,000 acres he and his brother inherited from their father, he insists they would never do it. “I’m not an environmentalist the way some extremists say they are,” said Schulte. “I know how fortunate, even spoiled, I may seem by all this, but I know this environment. I’m with it, all the time. No one could care more for it.” When the proponents of the “Gaviota Coast,” which he regards as a pure invention, came up suddenly last year with maps showing new trails and access cutting through the private property of himself and others, Schulte was stunned and furious. “I’m sitting there at this meeting, and they start treating us like little children, breaking us up into small groups to meet with these Park representatives with big pads saying, ‘Okay, what would you like to see on the Gaviota Coast?’” It was an old trick, often used in the Babbitt administration, to provide an illusion of public participation in a foregone conclusion suddenly last year with maps showing new trails and access cutting through the private property of himself and others, Schulte was stunned and furious. “I’m sitting there at this meeting, and they start treating us like little children, breaking us up into small groups to meet with these Park representatives with big pads saying, ‘Okay, what would you like to see on the Gaviota Coast?’” It was an old trick, often used in the Babbitt administration, to provide an illusion of public participation in a foregone conclusion with the help of so-called “facilitators” to resolve disputes. Schulte didn’t go along.

Oddly enough, John Buttney almost echoes Schulte’s words. “I don’t want to see more federal authority imposed here in any way,” said the so-called “sixth supervisor.” “To me it’s a matter of making sure we can protect ourselves for continuing on in the same way we have.” He too, like all the rest, concedes that Santa Barbara regulations over land use are already among the toughest in the nation, and if they are not tough enough, the State Coastal Commission is just as stringent on new development. Runaway ideas for some new federal designation, he said, are not really part of his or the Board of Supervisors agenda, even though he is partially responsible for them. It helps influence his current opinion, perhaps, that a recall petition has been initiated to remove his boss from office. Buttney was one of those who pulled the cork, setting loose a swarm of environmental attention on northern Santa Barbara County thatalready has caused one farmer, Bob Campbell, sleepless nights because an endangered salamander was found in one of his key pastures. Nobody even looks at frogs in their streams any more. And just at the end of last year, the Tucson-based Center for Biological Diversity filed suit to force federal habitat protection of some 67,000 acres in the same coast region where they say three species of endangered grasses have been found.

There is a mild irony in all this that, despite its somewhat exclusive nature, the north Santa Barbara coast has been generous before in giving up private property to the federal government. In World War II, several ranchers, including Leroy Scolari’s family, relinquished thousands of acres for what they thought would be the temporary establishment of Camp Cook. It is today Vandenberg Air Force Base, site of missile testing through the cold war and now the northern edge of the proposed “Gaviota National Seashore.”

“We all have to know,” Lanny Stableford said grimly, “that once the feds get a foot in the door, they will only take more.”

Later that night, in a remote schoolhouse further up 101 where the vaulted ceiling of the gym and auditorium reflects its Spanish heritage, there sits John Buttney along with Lanny and Bernie Stableford and Jenifer McNabb and Leroy Scolari as well as half a dozen other farmers, ranchers, and property owners and a couple of self-stated environmentalists. They have gathered there in the latest of endless meetings as a “Common Ground” committee so they can find some way to better communicate with the Sierra Club and others who are now pressing to make the “Gaviota Seashore” a national campaign. Incredibly, the “Common Ground” committee is there to “audition” professional “facilitators” for their skills at resolving public disputes. None of the candidates seems to have a clue of what it’s all about. Out of the bottle, the genie must giggle.. Tim Findley is an investigative reporter who lives in Fallon, Nev. He has worked for the San Francisco Chronicle and Rolling Stone. He used to be considered an urban bleeding-heart liberal; now he’s accused of being a “right-wing redneck” and other things he’s never even thought about. “That,” Findley says, “is what writing for RANGE has done to my reputation.” |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Spring 2002 Contents To Subscribe: Please click here or call 1-800-RANGE-4-U for a special web price Copyright © 1998-2005 RANGE magazine For problems or questions regarding this site, please contact Dolphin Enterprises. last page update: 04.03.05 |

|||