|  |

| [an error occurred while processing this directive] | |

| [an error occurred while processing this directive] |

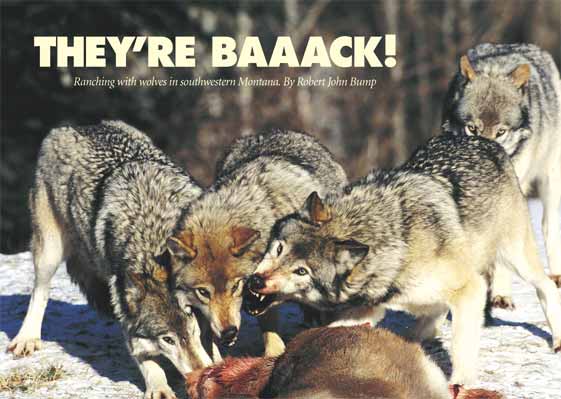

Everybody knew Uncle Sam's pet gray wolves would get into trouble with the neighbors in southwest Montana. That's why wolves just about went extinct in the 1930s. Montana sheep ranchers have had plenty to worry about, what with drought, foreign imports, wool prices and the economy—and now the big bad wolf is baaack. When Little Red Riding Hood said to the wolf, “My, what big teeth you have!” she could have been talking about the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS) and the Endangered Species Act. By government accounts, FWS has spent $17 million putting the endangered gray wolf back on the land. Thirty-two wolf immigrants, supplied by Canada, were released in Yellowstone National Park in 1995 and 1996. Central Idaho got 47 more. Seven years after FWS first opened the gate for the gray wolves, Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks biologist Ken Hamlin says, “The minimal number of wolves in the three-state area [Montana, Idaho and Wyoming] is currently between 650-700 in 80 packs, including 43 breeding pairs.” Federal officials estimate that Montana alone has 183 wolves in 35 packs with about 16 breeding pairs. It seems gray wolves are propagating themselves right off the endangered species list. FWS’s Druid, Gravelly, Freezeout and other unnamed wolf packs have now expanded their home range to include John Helle’s sheep in their prey base. Helle knows what it’s like to live with wolves and the FWS. The Helle and Rebish families arrived in Montana in the late 1800s. They operate both separately and together as Helle Livestock, and have tried to coexist with Uncle Sam’s “endangered” wolves, as their ancestors did with the wolves’ predecessors more than a century ago. It probably would have seemed ridiculous to the immigrant families that their descendants would have to employ a multinational force of Peruvian herders, guard llamas, and Turkish Akbash and Great Pyrenees guard dogs just to protect their sheep from wolves deliberately forced upon them by the U.S. government.

The Rebic family came to Montana from Austria looking for the American dream in the late 1880s. Their descendants have been ranching in southwestern Montana ever since. In 1891, Joseph Rebich (as it was with so many immigrants, his surname spelling changed over time in America from Rebic to Rebich to Rebish) married Catherine Mihelick, also of Austria. They ranched south of Dillon, Mont., for many years. Joseph was seriously and permanently injured in a logging accident in 1907. He passed away unexpectedly in 1921 leaving his widow Katie with eight children. Among the children were two brothers, Peter and George Rebish, who were forced to drop out of school at ages 12 and 14 to find work on area ranches. They formed a lifelong ranching partnership and with hard work and a little luck they started out in the sheep business on their own in 1928, trading a Model T for 50 head of cutback ewe lambs. In the beginning, they ran their sheep in a community band and did the herding. In 1937, they married two sisters, who were also of Austrian descent. Annie Kranatz married George, Agnes married Peter. Together, the two couples bought a ranch three miles north of Dillon and began Rebish Brothers. In the 1940s they bought Rambouillet sheep, a breed still favored on the ranch for its fine wool, longevity, and easy herding. Ranch life for them and Helle Livestock follows the pattern established by the Rebish brothers, starting in the early spring with shearing, then lambing, docking, trailing the sheep to the summer ranges—much of which is within the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest—and trailing them home in the fall. Their families’ sheep operation includes 7,500 sheep in four bands roaming private and national forest lands, in some areas just 30 miles west of the Yellowstone National Park boundary. The Rebish brothers thought they’d seen the last of wolves on their ranges in the 1930s. But Pete and George survived to see the gray wolf declared “endangered” under the Endangered Species Act in 1974. This was the initial step in the wolves’ return. Their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren are all becoming quite experienced in the ways of the wolf, and of those who put them back into their lives. “Wolves don’t need a habitat, what they need is a prey base,” John Helle says. “Our sheep have become that prey base. Wildlife in the state became part of the prey base also.” Helle is a rancher, and his instinct is to try and keep animals alive, rather than kill them. But after suffering several major losses to wolves last year, he legally killed a male gray wolf among his woolly prey base. Later, using a helicopter, FWS agents killed a female and her grown young, caught preying on the Helles’ sheep. The Washington D.C.-based group Defenders of Wildlife (DOW) have pledged to help ranchers by assisting to offset the costs of wolf damage to livestock. The cost has been going up as the wolves expand their range. In 2002, DOW spent slightly over $50,000 in compensation to livestock producers. Sheep ranchers see this compensation as inadequate. “We’re not in the business to raise sheep for the wolves,” Helle says. “Many kills can’t be confirmed, and there are other, hidden costs that can’t even be measured, let alone compensated.” In the seven years since wolf reintroduction, he reckons they have lost more than $10,000 worth of sheep to wolves and a few good sheepdogs as well. Often, too much of the animal is taken and wolf predation cannot be verified according to the documentation requirements for compensation. Payment for the few losses that have been verified often comes months later. Dick Everett, president of the Montana Woolgrowers Association, thinks Montana sheep ranchers like Helle could well be endangered species themselves. At last count Montana has just 1,700 sheep and lamb ranchers still in business, 100 fewer than the year before. “In 1910, Montana had a record high 5.3 million sheep,” Everett says. “Montana’s lamb count on January 2003, dipped to only 300,000 head, down 10 percent from last year. This decline is due to many factors, but it shows the pressure that sheep ranchers like the Helles are under in this country.” According to Carolyn Simes, spokesperson for Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks, the Helles may have some help on the way in the form of Montana’s Gray Wolf draft plan. In order to get the wolf off the endangered species list, Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming need to come up with wolf management plans that meet with FWS approval. The feds would then begin a transfer of management authority to the states. The goal set in the recovery plan was 30 breeding pairs in the three-state area of Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming for three successive years. The wolves first met the target in 2000. As of 2003, they were still thriving.

In March and May, 2003, MFWP held public workshops concerning the Montana Gray Wolf Conservation Plan as part of its 420-page draft environmental impact report. At 14 locations throughout Montana, more than 478 people attended, giving 1,595 recorded comments and 5,428 statements. MFWP also received 355 letters and 99 e-mails, indicating how emotionally charged the wolf-reintroduction issue remains. The politicians got the message and have tried to get serious about figuring out how wolves will be managed under state laws. The 58th Montana legislature enacted some wolf-related bills last year. Dan Fuchs (R) from Billings and Joe Balyeat (R) from Bozeman, among others, successfully sponsored House Bills 262 and 283. HB 262 clarified the policy of the MFWP by establishing policy and rules for “Management of Large Predators” (specifically including wolves): “Large predators must be managed primarily to preserve huntable species of large game and to protect livestock, pets, and people.” HB 283 directed the state attorney general to analyze state delisting options and possible litigation scenarios for recovery of damages and costs associated with wolf reintroduction, seeking compensation from FWS for the cost of wolf management and damage to domestic livestock. Some fear that these Montana bills, along with politics elsewhere, might derail the process of delisting through 2004, or longer. Even changing the status of wolves from “endangered” to “threatened” will still require FWS monitoring, to be sure numbers don’t drop below “sustainable” levels, so the gray wolf won’t become endangered again. The wolf is here to stay, along with its “watchdog” FWS, special-interest groups, and all those hidden costs. Biologically, the gray wolf has recovered, a howling conservation success. Meanwhile the Helles’ non-union spike-collared sheepdogs are watching over ungrateful sheep, twitching in their sleep, patiently and painfully waiting for the laws of man to keep pace with the laws of nature. Garlic farmer Robert John Bump retired from the BLM in 1999. The soil scientist and his wife (a former range conservationist with the U.S. Forest Service) live in Dillon, Mont. |

| [an error occurred while processing this directive] |