|

|

|

| Subscriptions click here for 20% off! | E-Mail: info@rangemagazine.com |

|

|

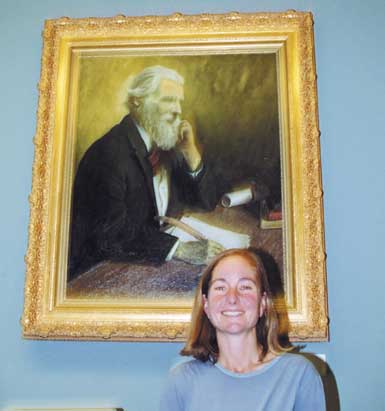

Like Sierra Club founder John Muir, Jennifer Ferenstein is complex. She prefers the velvet glove, even when she’s going for the throat. |

|

|

|

John Muir wasn’t just a mere eccentric. Maybe he climbed pine trees in howling windstorms just to show off, but even those who admired him—and most did—John Muir wasn’t just a mere eccentric. Maybe he climbed pine trees in howling windstorms just to show off, but even those who admired him—and most did—realized that Muir’s effusive relationship with nature went way beyond simple science. That was God himself that Muir felt swaying the thinning trunk between himself and oblivion.

Still, we forget that the founder of the Sierra Club was also a farmer, and by all accounts, a pretty good one. He understood the need to till and harvest the land as much as he was awed and humbled by the primitive power of its natural state. John Muir could be one complex pain in the ass. Doesn’t it seem fair to wonder, then, what he might think of the deceptively frail-seeming young woman who holds domain in the 21st Century as president of the most potent membership-directed conservation organization in the world? Thirty-six-year-old Jennifer Ferenstein won election to the Board of Directors of the Sierra Club by vote of the club’s 700,000 members. Three years later, in 2001, the 15-member board elected her as their president. Her loving grandparents on a ranch in Oregon immediately offered their congratulations, although her grandfather still regards her as having leadership over an excessively large group of “flower sniffers.” Ferenstein’s one-year election might not mean that the biology grad from intellectually elite Reed College in Oregon with a master’s in Environmental Studies from the University of Montana can even talk back too directly to Sierra Club Executive Director Carl Pope. Like Muir, however, she’s not just a simple forgotten-later tree-hugger either. Sit with her in the San Francisco office she actually seldom occupies, and you can tell by the way she abruptly fields the pestering phone calls and doorway visits that she knows she’s in charge. She would rather be in Missoula, where she is most often, doing the full-time work of a world-linked nonprofit corporation far beyond the imagination of Muir himself. But, if she must, she can put an eager San Francisco underling in his place with no more than a softly-sharpened word—“later.” A “pragmatist,” she calls herself, someone who grew up spending summers on her grandparents’ ranch in Wheeler County, Ore., where she helped shear the sheep and sometimes butcher lambs on a neighbor’s ranch. “So, I’m not afraid of death. I know where meat comes from, and I still go hunting,” she says. “But, frankly, it’s the magnitude of change that I feel I have an obligation to respond to, and to try to educate people about living a life that’s constructive, instead of destructive.” The meaning of that appears to be somewhere between cherishing a past of family agriculture and not letting it get much beyond the fences of her own memory. She was undeniably a privileged child, the daughter of a corporate lawyer in San Francisco, who first recognized the relentless stretch of growth and urban sprawl while riding her horse in the Berkeley hills. On the Oregon ranch where her mother was raised, she took no special attention of what damage the cattle might do, but she silently witnessed the way that business got done. “I think a lot about greed, and big businesses and changes I don’t think any of us really want to see. It’s the magnitude of change that concerns me, the rate for example, that we use fossil fuels. On my grandfather’s ranch, I remember the guys from the petrochemical industry coming out selling herbicides and insecticides and various fertilizers. It was like they were pushing drugs—‘Hey, what, John, try this, try that’—and I think some of those things improved productivity for him over the short term. But I saw a lot of rank things go on that I don’t think were healthy in the long run for the soils or the animals or for my family.” Jennifer, remember, was only born in 1965, well along not only in the history of the Sierra Club, but in the founding passion of the newer “environmentalist movement” itself, just a little too young to have played a part in spotted owl saving of old-growth forests. What she was learning in those impressionable years had to be a blend between the corporate power of her father’s high-rise office with the common strength of her grandfather’s fourth-generation ranch. What motivated her, she says, was not the small change she saw in Berkeley or in Oregon, but the “magnitude” of it coming in the future. What killed John Muir, they say, was an all-out and still-unforgotten battle between the Sierra Club and the City of San Francisco over damming what Muir called the “cathedral” of the Hetch Hetchy Valley near Yosemite. Muir lost, but the Sierra Club still hasn’t given up on someday wrecking that dam. Ferenstein, however, would never be that strident. On public lands and old-growth forests, she’s as “green” as they get, but she rejects the idea that the times must “polarize” the issue between environmentalists and property owners over how land gets used. “Oh, I see the fear [among property-right owners],” she says, “but I think that fear is more because of the rapidly changing economy and the world we live in. I think that environmentalists are an easy scapegoat for problems that have much more to do with agribusiness coming in and driving out family farmers or from factory farms destroying family ways of life than it should be from environmentalists.” On habitat issues, endangered species, and multiple use of public lands, Ferenstein insists the two sides can come to some agreement. “We don’t have any other choice.” But the young, bright, pragmatist president of the Sierra Club is no fool in acknowledging that the Club itself has spawned radical extremists such as David Foreman (a former member of the board) and others with agendas clearly meant to destroy rural livelihoods. “There are many environmental groups now that we work with,” she says. “We share information, ideas, but [the environmental movement] is not always the monolith people think it is.” She won’t directly admit to being uncomfortable with Foreman or with the radical agendas of Earth First! and the Wildlands Project, because Sierra Club policy, approved by the membership, is diplomatically aware of its own “moderate” image in a general movement with a sprawl of its own. “We don’t want to take anyone’s land from them or drive anybody out of business,” Ferenstein assures. “We want to find a means to make it better for all of us—the people, the plants, the animals.” John Muir might have said something like that, though in much more florid language. Who, for that matter, would disagree? The fact remains, however, that a cultural confrontation even Muir didn’t imagine exists today between those who simply want to be left alone to make best use of their land and those who are convinced it can be done better if it must be used at all. Somebody like Andy Kerr and his National Public Lands Campaign uses warnings that sound like veiled threats to make the point—“it’s us or the courts”—he suggests. Ferenstein on behalf of the Sierra Club prefers the velvet glove, even when she’s going for the throat. Complex she is. Like Muir. She combined her science skills with a broadened sense of environmental law at the University of Montana and emerged with the sort of biology-based leadership style that skirts lightly around heavy politics of the kind that has torn up the Sierra Club before. She sees her own job, for example, to promote more participation in the democratic process of developing Sierra Club policy. “I mean, really, if ranchers want to see some real change and even protect themselves, they should join the Sierra Club and vote.” Yet she has no doubt that conflict is inevitable in the “struggle” for the environment, particularly between “rights versus privileges,” as, for example, canceling grazing permits in creation of new national monuments. “Those are public lands,” she says. “I think there is the question that there is not a lot left. In the early days we tended to protect the high country—the rocks and ice—but not necessarily the valleys and the riparian areas where people want to be as well as wildlife. Now, with more and more people, it’s those places that most need protecting, not the rocks and ice. Life is about displacement. People can change. We don’t advocate taking people’s property. It’s not part of our policy or desire. But there is a balance to be struck even in protecting the lowest denominator as part of protecting us all.” To Ferenstein, much of it comes down to making a decision about “what we need and what we want.” Do we really need the oil from Alaska? Do we need as many cattle in the West? And is the way we produce food now the best way to do it? “I think we need to look at sustainable promotion of agriculture,” she says. “I’m a big proponent of bio-regionalism. The closer you can live off the land and the products you can use, the better off we all are. I think that people, rather than force the world to bend to them, should adapt to the place where they choose to live.” Ferenstein herself buys mostly organic food, including beef, from local farmers in Montana, avoiding the big markets and their corporate muscle. Still, it’s another of those “Muirisms” that require a little thought before you instantly agree. “Bio-regionalism,” for example, might mean folks in Kansas should lose their taste for avocados, and folks in California might need a local substitute for Wonder bread. “Fact is,” says Ferenstein, “I think people in Montana can get along without strawberries in December.” Those “magnitude” things like big oil fuels are also a matter of scale to the Sierra Club president, who says she does not completely object to the use of fossil fuels, “but if everybody chooses to drive an SUV, they had better realize the consequences.” In short, Ferenstein is convinced that, “We have to sacrifice to survive.” Muir would certainly agree, but others could see the argument coming. If there is a clear heritage between that old man hanging onto the tip of his swaying pine tree and this young woman carefully engaging in diplomacy, maybe it is that they both find in nature and human behavior a certain welcome howling like the spirit of God himself. Now as then, though, it’s in the details where resides the devil. |

||

|

Spring 2002 Contents To Subscribe: Please click here or call 1-800-RANGE-4-U for a special web price Copyright © 1998-2005 RANGE magazine For problems or questions regarding this site, please contact Dolphin Enterprises. last page update: 04.03.05 |

|||