|

|

|

| Subscriptions click here for 20% off! | E-Mail: info@rangemagazine.com |

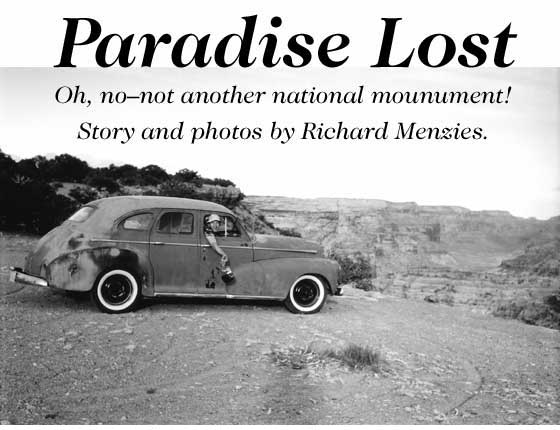

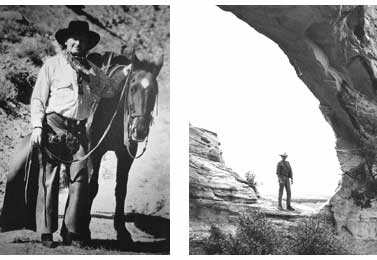

The year was 1964 and Clark Hunt and I were taking a big chance driving into the back country. For starters, we had no two-way radio, no global positioning device, no backup vehicle, no cell phone—not even a map. Moreover, my 1950 Mercury had no reverse gear, a condition which on a narrow road demanded a level of commitment rare in young people even then. Clark had been working a summer job with the BLM. (“Bums Like Me” was how he unfailingly described the agency.) His duties involved scouting out scenic spots along Interstate Highway 70, which at the time was naught but a line of survey stakes linking wonderful places with strange-sounding names: Black Box, Ghost Rocks, Secret Mesa, Rattlesnake Bench, Spotted Wolf Canyon; not to mention Molly’s Nipple, Nancy’s Nipple and half a dozen other suggestively shaped mounds destined to be renamed on future road maps in order to render the landscape suitable for family viewing. We said goodbye to pavement at Cleveland and headed southeast on a dirt road down a steadily deepening gorge called Buckhorn Draw. We followed in the tracks of Butch Cassidy, who made his getaway through the draw to Robbers Roost after snatching the Castle Gate Mine payroll in 1897. We crossed the San Rafael River on an improbably sited suspension bridge—a labor-intensive WPA project constructed during the Roosevelt Administration. By nightfall we had reached the Head of the Sinbad and were deep in the land that time forgot, a land that no one knew. Call it what you will—to us it was Paradise. We were alone, with no signs of habitation save a rustic, sod-roofed log cabin. Here and there stood rock cairns, miniature pyramids erected during the uranium boom of the fifties. Each claim marker contained a rusted Prince Albert tobacco tin and tucked inside each can was a yellowed parchment inscribed with numbers, cryptic symbols, and arrows pointing the way to the next Mi Vida. Clark’s father had staked several such claims in the Temple Mountain district, where each summer Clark and I would venture in order to conduct the obligatory annual “assessment work.” Assessment work at Temple Mountain entailed turning over a few shovelfuls of dirt, perhaps setting off a stick or two of dynamite. In Sinbad Country, however, nothing got blown up except our adolescent egos. I mean, we were the

masters of all we surveyed! We were the only humans within a radius of a hundred miles—or so it seemed. From the heady heights of double D-sized hills, we gazed upon vistas of heartbreaking beauty. To the west lay the snowcapped Wasatch Plateau, to the north and east stretched the castellated arc of the Book Cliffs. To the southeast rose the conical peaks of the Henry Mountains, home of the West’s only free-roaming buffalo herd. Directly east lay the spectacular stegosaurus-shaped sandstone escarpment known as the San Rafael Reef. And beyond the reef, barely visible in a haze of vermillion and pink, Arches National Monument—presided over at the time by a cantankerous park ranger by the name of Edward Abbey. In 1971, only four years after Abbey in the preface to “Desert Solitaire” ordered the general public to stay away from “the most beautiful place on earth,” President Richard Nixon signed into law an act designating Arches National

Monument a national park. I seriously doubt that Tricky Dick had ever set foot in southeastern Utah, let alone crawled, “on hands and knees, over the sandstone and through the thornbush and cactus,” which was the mode of transportation recommended by Edward Abbey. In September of 1996, President Bill Clinton signed into being still another national monument. From where Bill was standing, on the south rim of Arizona’s Grand Canyon, he couldn’t see that portion of southern Utah he was allegedly preserving for posterity, nor hear the cries of native protestors. No matter—the 1.7-million-acre Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument played well among conservation minded urbanites and helped ensure Slick Willy’s re-election to the White House. Today a proposal is underfoot to designate 620,000 acres of the San Rafael Swell a national monument. This time around, the plan is being pushed by Utah’s governor Mike Leavitt, with backing from President Bush and members of the Emery County Commission and Public Land Council. Yet even though the latest monument proposal appears to have originated locally, still it has not met with unanimous local support. “We have seen the manipulation of our public lands for political gain before, and we don’t like it,” writes Brian Hawthorne, executive director of the Utah Shared Access Alliance, in a letter to the Salt Lake Tribune. “The small

communities and unique culture that exists in our rural areas are important to us. We must have management that strikes the proper balance between protection and conservation, and access to and use of resources.” In the Salt Lake City neighborhood where I now live, within walking distance of 15 gourmet coffee shops, the buzz on the street is the more monuments, the merrier. By and large my neighbors are young urban professionals, each with his own sport utility vehicle topped by a mountain bike rack—and whenever they hear the magic words “protect” and “preserve” they automatically begin to salivate. Because I, too, live in the city and hold stock in REI, it is assumed I should likewise be seduced by the magic “p” words. But, alas, I’m a former country bumpkin who had the great good fortune to “discover” canyon country long before the Sierra Club and Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance appeared on the scene. As a result, whenever I encounter those familiar “p” words, I only get moist around the eyes. I think not of preservation and protection but of paternalistic posturing, power plays, party politics, people, pavement, pollution. I also think of Paradise, and the way things used to be. Richard Menzies is, like the editor, on perpetual walkabout. He’s in an orange, flower-strewn Volkswagen bus. She’s on a 750 Yamaha. |

|||||||||||||||

|

Summer 2002 Contents To Subscribe: Please click here or call 1-800-RANGE-4-U for a special web price Copyright © 1998-2005 RANGE magazine For problems or questions regarding this site, please contact Dolphin Enterprises. last page update: 04.03.05 |

|||