|

|

|

| Subscriptions click here for 20% off! | E-Mail: info@rangemagazine.com |

Aloha + Shazam = OwyheeTHE RANCHERS WERE GIVEN AN IMPOSSIBLE FOUR DAYS TO BUILD THE FENCE. NOT FOR THE FIRST OR LAST TIME, THE BLM UNDERESTIMATED THE COMMUNITY. BY TIM FINDLEYOdd place, the Owyhee. It runs rugged and wild across sharp rising mountains and deeply dipping green valleys in southwest Idaho into a corner of Oregon and a nip of Nevada. Shoshone-Paiute country, still mostly untamed beyond choice roadside glens like Jordan Valley, Ore., it seems open to roaming, almost forgotten. You would think in such a muse that Owyhee derives its name from a Native American word chiming with

With the help of a federal Clinton-appointed judge who blatantly admits his own bias against ranchers, 68 separate permit holdings on Bureau of Land Management (BLM) allotments in this region have been challenged and threatened with just about as many individual claims against their existence over the last decade. From overgrazing to endangered species to cowpies on a stream bed, Marvel has gone at it in so many different ways and with such relentless, pestering attention that even the BLM issued an official directive instructing employees not to talk to him at all any more, except by letter. But if they’re not talking to Marvel any more, BLM authorities in the Owyhee must still be listening to somebody for advice on the contorted and sometimes absurd ways they have found to force cattle off the range under terms of their own Resource Management Plan (RMP). Like other plans invented in the Babbitt administration, it aims to control water resources, restrict AUMs (Animal Units Monthly) and shorten grazing seasons. Even BLM Management Specialist Bill Reimers acknowledges that implementing the plan will “make it difficult for a number of them [the ranchers] to stay in business.” Reimers, sounding sympathetic, claims he is “only carrying out the laws.” Just as elsewhere in the West, the dire economic objectives of the plan first hinted at a decade ago were recognized by Owyhee County authorities who authorized their own resource commission and stood ready for the battle - in and out of court if necessary. But it would come about in strange little skirmishes that even today leave open the question of who is writing the “laws.” Take the minor monument of the cattle guard we call “Hillary” that rests in slightly fading, but still bright-yellow painted iron far up on a barely tracked road across the so-called Cliffs allotment. It was actually Colorado Congresswoman Patricia Schroeder who once suggested in jest so many “cattle guards” in the West ought to be retrained for better employment, but Hillary cheered her on, and there’s something about the Cliffs’ cattle guard that deserves more regal status. For one thing, it is probably the loneliest cattle guard in the West. Not so much because there are no cattle there now, but because there is no fence on either side of it that would make it necessary at all. Tim Lowry and two other permit holders on the Cliffs put it there with the help of an astonishing community effort that erected the remote three-mile fence in less than four days. “[Fellow Cliffs permittee] Jeannie Stanford remembers getting a call the next morning from [former BLM manager John] Fend telling her they wouldn’t give us any more time,” recalled Lowry. “‘S’okay, John,’ she said. ‘The fence is done.’ There was just this long silence. ‘What about the cattle guard?’ he said finally. ‘Yep, John. Cattle guard too.’” That obviously wasn’t what the BLM expected when they first began dragging their feet in 1991 over the offer of the permit holders to divide the allotment into three separate pastures, allowing at least one to be rested for a season. It was a good idea and a pro-environmental concept, but not part of the BLM management plan, and the

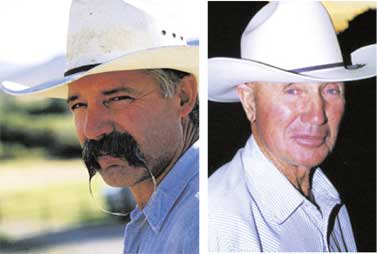

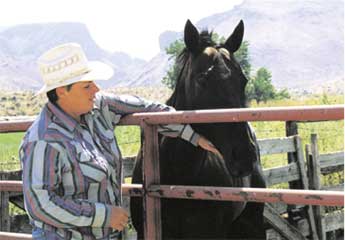

And that is what is most infuriating of all about the battles of the Owyhee these days. Despite the lengths to which ranchers on their own have tried to initiate better management that might anticipate the extremes Marvel and his Idaho Watersheds Project (IWP) will find for eliminating them, there inevitably follows a re-encounter with new BLM policies bound to mismanage the ranchers out of business anyway. “The court’s decision never states that its imposition of the interim measures was based on evidence of environmental damage submitted by IWP,” wrote Federal Judge B. Lynn Winmill this year in one of his remarkably contorted excuses for refusing even to grant the ranchers a hearing on Marvel’s latest attempt to block renewal of all 68 grazing permits in the Owyhee. “Instead, the interim measures were employed solely because they offered a BLM-approved, less drastic alternative to the complete prohibition of all grazing.” The “interim measures,” some of them written on the spot, amount to the same ranch-killing management plan that Owyhee has been fighting for the last 10 years. Judge Winmill refused even to examine evidence from ranchers revealing its environmental flaws. In other words, forget due process in the Owyhee. Just be happy for now that the BLM doesn’t much like Jon Marvel either. Judge Winmill, a busy man about town in Boise, makes no pretenses of having spent so much as an afternoon drive in examining the actual environmental condition of the region. Instead, Winmill’s decisions have dodged the wrath - or reward - of Marvel’s hyper-demands by giving the BLM unbridled, and unchallenged, authority to accomplish Marvel’s aims on their own bureaucratic schedule. The ranchers have watched in part with amazement since, as the BLM raced with helicopter “surveys” and short-science stream visits to justify their measures, while the ranchers’ own science on the subject is entrusted to lawyers who so far can’t get the court to even look at it. For a hard-leather man with a longhorn handlebar mustache like Tim Lowry, it’s a tiresome and expensive game run by people who don’t belong in the raw beauty of his country any more than did those Hawaiians. Since the 1970s he has run his own ranch alongside the LU spread of his father, Bill Lowry, in the secluded meadows of Pleasant Valley, Ida., just across the Oregon line. Seventeen kids, grades one through eight, go to the local school, and most of them never leave a dirt road to get there. It’s where Bill and Tim and their combined families always hoped they could live someday, just far enough apart from everybody else to make them feel neighborly. Even the year of drought supposedly parching western Oregon this year seemed to leave Pleasant Valley blissfully apart. In mid-August when Senator Larry Craig came out to talk to ranchers at the schoolhouse, the valley fields were still an eye-aching green, knee deep in grass where a group of bucks big enough to be

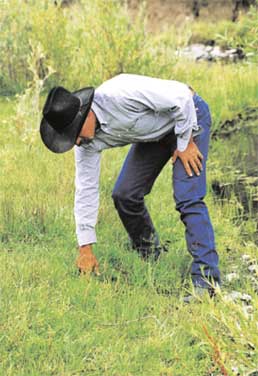

“What they want is just to make it a bad year for us,” said Lowry, measuring his own large palm against the August growth along the stream. “They know we can’t just put cattle out for a month and bring them right back in this country. They know it’s just one more try to run us out of business.” By measures Judge Winmill called “less drastic” than what Marvel wants. Across the stretch of highway leading toward Boise, another full 50 miles from the Cliffs, Richard and Connie Brandau have their own problems with the BLM and “Marvel” science made to fit. In the steep, dry canyons

Among friends, gathered around a hitching post with the friendly Brandau dogs running under foot, the “renegades” swap familiar stories among themselves, occasionally punctuated by Connie’s more

A series of BLM managers in the Owyhees have heard from her and others in the long process of adding new restrictions supposedly, but seldom, based on consultation with the ranchers themselves. Nobody doubts that Connie is correct, and if they haven’t quite had the nerve to say so themselves, it is in part because the organization of 68 permittees has learned how to designate tasks in their joint battle against Marvel and the BLM. Privately, the bureaucrats call them “Owyhee renegades.” The truth in this part of Idaho, however, is that virtually all elected authorities from the sheriff up to their U.S. senator regard the actions of the BLM in the Owyhee districts as a relentless exertion of arbitrary power and even outright collusion with the ranchers’ environmentalist opponents. That was a conclusion Sheriff Gary Aman came to a couple of years ago when one of his deputies stopped a

Tim Findley is an investigative reporter who lives in Fallon, Nev. He has worked for the San Francisco Chronicle and Rolling Stone. He used to be considered an urban bleeding heart liberal; now he’s accused of being a “right-wing redneck” and other things he’s never even thought about. “That,” Findley says, “is what writing for Range has done to my reputation.” |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

To Subscribe: Please click here or call 1-800-RANGE-4-U for a special web price Copyright © 1998-2005 RANGE magazine For problems or questions regarding this site, please contact Dolphin Enterprises. last page update: 04.03.05 |

|||